This section contains notes about some of the most useful things from the std namespace. The C++ standard library also contains the entire C standard library, each header being available through <c*>, e.g. <cstdlib>, which in C is equivalent to <stdlib.h>, and <cmath>, which in C is equivalent to <math.h>.

See all C++ Standard Library headers.

<string> [TODO]

There is no built-in string type in C++, but the standard library provides std::string in <string>. Note that string literals on the other hand are part of the language itself, their data type is const char*.

The set of methods available to the std::string class is similar to the methods available to std::vector, plus a few more special string manipulation methods and operator support like +, <<, >>.

// Main operations

s1 + s2 // Concatentation

s1.append(s2) // Alternative to + operator

// TODO: https://www.cplusplus.com/reference/string/string/compare/

s1.compare(s2)

s1.compare(s2, pos

s.substr(startPos, runLen) // Returns the substring from inclusive startPos onwards for runLen characters

//TODO: more string ops https://www.cplusplus.com/reference/string/string/

s.find

s.find_first_of

s.find_first_not_of

s.find_last_of

s.find_last_not_of

>

// Others

s.copy()

char c;

std::isdigit(c) // Returns true if the string consists of a valid digit.

std::isalnum(c)

std::isspace(c)Raw Strings:

There are raw string literals just like in Python where everything inside the string is treated as raw characters, not special characters. This means you won’t have to escape any special characters with backslash and they’ll all lose their meaning. This is especially useful when defining strings containing regex patterns which contain a bunch of backslashes.

The format for defining a raw string literal is: .

std::string my_raw_str = R"(my raw string)"; // → "my raw string"- String formatting with

std::stringstreamfrom<sstream>std::stringstream fmt; fmt << "hello " << 10; std::string formatted_str << fmt.str();

str.find_first_of

std::string::npos

std::string_view vs std::string

-

A

string_viewis nothing but a pointer to a string and a length. It serves as basically a read-only substring of an underlying string. -

string_viewcan offer better performance thanstring. -

Why not just use

const string&? Because that has to refer to astd::stringexactly, not a char array,const char*,vector<char>etc., which means that a newstd::stringinstance must be created from these other ‘sequence of char’ formats, which is potentially expensive. -

You can do

constexpr std::string_view s = "…", but notconstexpr std::string s = "…" -

You can get string literals of type

std::stringby suffixing a regular string literal withs, e.g."Hello"s. -

You can get

string_viewliterals by suffixing string literals withsv, e.g."Hello"sv.

STL Containers

The STL (standard template library) contains highly efficient generic data structures and algorithms. The STL encompasses many headers like: <array>, <stack>, <vector>, etc.

<vector>

‘Vector’ isn’t the best name. It should be called ‘ArrayList’ or ‘DynamicArray’. It is implemented with an array under the hood.

- To resize the underlying array, a larger memory block is allocated and all items in the original array are copied over to the new larger one. This is an operation.

- Vectors consume more memory than arrays, but offers methods for runtime resizing.

#include <vector>

// Initialisation

vector<int> a = { 1, 2, 3 };

// Main methods

a.insert(posIter, b) // O(1) - Inserts b at posIter

a.insert(posIter, it1, it2) // Inserts elements from it1 to it2 at posIter

a.erase(posIter) // Deletes item at posIter

a.erase(startIter, endIter) // Deletes all elements in range from inclusive startIter to exclusive endIter

a.push_back(b) // O(1) - Append

a.pop_back() // O(1) - Pop from end

a.front() // O(1) - Peek front

a.back() // O(1) - Peek back

a[i] // O(1) - Access item at an index (the same way you would for arrays)

a.at(i) // Alternative to []. It throws an exception for out of bounds access

// Iterators

a.begin() // Iterator starting from first element (index 0)

a.end() // Iterator starting from last element

a.rbegin() // Reversed

a.rend()

a.cbegin() // Read-only iterator

a.cend()

// Properties

a.size()

a.empty()

a.max_size()

a.capacity()Slicing and splicing:

// Slicing

template<typename T>

vector<T> slice(vector<T> vec, int start, int end) {

// Returns a new vector from inclusive start to exclusive end

auto first = vec.cbegin() + start;

auto last = vec.cbegin() + end;

vector<T> sliced(first, last);

return sliced;

}

// Splicing

vector<int> a = { 1, 2, 3};

vector<int> b = { 4, 5 };

a.insert(a.begin() + 1, b.begin(), b.end()); // a is now { 1, 4, 5, 2, 3 }

a.erase(a.begin() + 2, a.begin() + 3); // a is now { 1, 4, 2, 3 } <set>

Stores elements in sorted order without duplicates. For most use cases, you probably want to use unordered_set instead, which has more favourable time complexities.

- The underlying implementation uses a balanced tree.

set<T> s;

s.insert(T elem) // O(logn) - Inserts element

s.find(T elem) // O(logn) - Gets an element

// Returns an iterator which points to the value if it was

// found, otherwise it points to s.end().

s.size() // O(1) - Cardinality.<unordered_set>

Same as std::set from <set>, just unordered.

unordered_set<T> s;

// CRUD:

s.insert(T elem) // O(1)

s.find(T elem) // O(1)

s.erase()

// Properties:

s.size() // O(1)

s.empty()- Uses a hash table as the underlying data structure.

<map>

A data structure mapping a set of keys to values. This one maintains order of keys. If this is irrelevant (which it usually is), use unordered_map instead.

- Implemented with a self-balancing binary search tree.

map<string, int> m;

// Main operations

m.insert(pair) // Takes in std::pair<keyT, valT>

m[key] = val // More straightforward way to add key-value pairs

m.erase(key) // Deletes key-value pair by key. Doesn't fail if the key doesn't exist

// Iterators

m.begin()

m.end()

// ... and all the other ones available to classes like std::vector

// Properties

m.size()

m.max_size()

m.empty()- There are multiple ways to insert key-value pairs into a map, eg.

insert(),[ ]operator,emplace(), etc.

Usage example:

// Adding key-value pairs:

map<string, int> frequencies;

frequencies["Hello"] = 4;

frequencies["World"] = 3;

int val = frequencies["World"];

// Iterating through key-value pairs:

for (auto it = frequencies.begin(); it != frequencies.end(); ++it)

cout << it->first << " : " << it->second << endl;<unordered_map>

The interface is very similar to std::map from <map>, however it offers a few more lower-level methods like bucket_count(), load_factor(), etc.

<array>

// Initialisation

int nums[3];

int nums[3] = { 1, 2, 3 }; // [1, 2, 3]

int nums[] = { 1, 2, 3 }; // [1, 2, 3]

int nums[3] = { 1 }; // [1, 0, 0]

int nums[3] = { }; // [0, 0, 0]

// TODO: Utility functions

std::fill_n(nums, 3, -1);

- To get the size of an array, you’d need to do . It is almost always recommended to use

std::vectorover regular arrays.

<stack>

#include <stack>

stack<int> s;

// Main methods

s.push(item);

s.top() // Reads the top element

s.pop() // Removes the top element. Doesn't actually return anything

s.empty()

s.size()<queue>

#include <queue>

queue<int> q;

// Main methods

q.push()

q.front() // Reads the next element

q.back() // Reads the last element

q.pop() // Removes the top element. Doesn't actually return anything

q.empty()

q.size()<tuple>

// Construct tuples with `std::make_tuple`

std::tuple<string, int> person("Andrew", 42);

// Access tuple values with `std::get`. Tuples don't work with the subscript operator [] unfortunately. Reason: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/32606464/why-can-we-not-access-elements-of-a-tuple-by-index.

cout << std::get<0>(person) << endl;

cout << std::get<1>(person) << endl;

// You can also construct tuples with `std::make_tuple`. This is better

// when you want to pass a tuple r-value to a function because `make_tuple`

// can infer types. See: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/34180636/what-is-the-reason-for-stdmake-tuple

std::tuple<string, int> person = std::make_tuple("Andrew", 42);<algorithm> [TODO]

I/O [TODO]

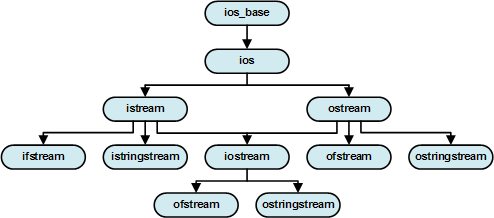

In computer science, a stream is an abstraction that represents a sequence of data that arrives over time (much like a conveyor belt delivering items). In C++, this stream abstraction is how we work with reading/writing characters coming from an input stream (eg. user input on the terminal or a file in read mode) or being written to an output stream (eg. the terminal or a file in write mode).

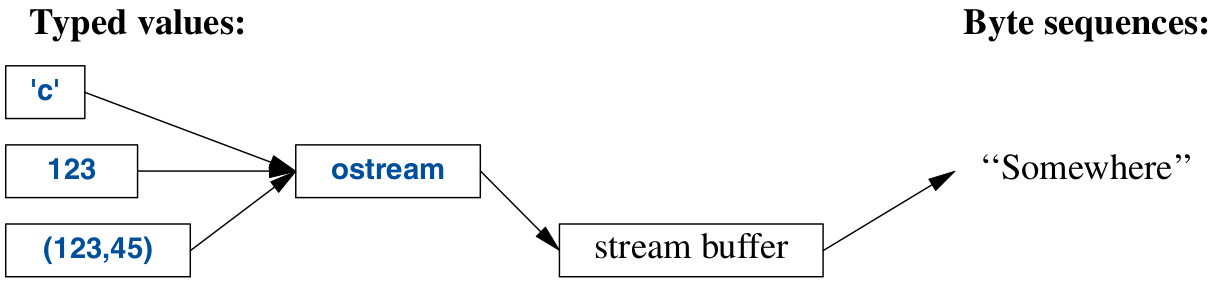

ostream

An ostream serialises typed values as bytes and dumps them somewhere.

- The ‘put to’ operator

<<is used on objects of typeostream. std::coutandstd::errare both objects of typeostream.

-

You can chain the put-to operator

<<because the result of an expression likecout << “Hello”is itself anostream.cout << "Hello, " << "world.\n"; -

You can overload the << operator for your own classes. Example

class Person { public: Person(std::string name, int age) : name_(name), age_(age) { } std::string Serialise() const { return "(name: " + name_ + ")"; } private: std::string name_; int age_; }; ostream& operator<<(ostream& os, const Person& person) { os << person.Serialise(); return os; } int main() { Person person("Andrew", 42); std::cout << person << std::endl; return 0; }

iomanip [TODO]

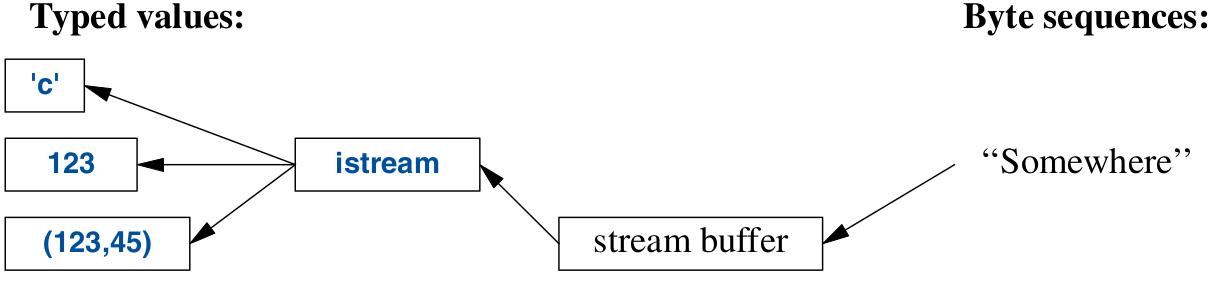

istream

An istream takes in bytes and converts it to typed values.

- The ‘get from’ operator

>>is used as an input operator std::cinis the standard input stream

-

Formatted extraction: The type of the RHS of the ‘get from’ operator determines what input is accepted

int i; cin >> i; // Expects an integer value to be supplied double j; cin >> j; // Expects a floating point value to be supplied-

You can chain the get-from operator

>>just like for put-to<<.cin >> i >> j; // Expects an integer, and then a double -

The user input can be space-separated, new-line-separated or tab-separated integers. There can be any number of ’ ’, ‘\n’, ‘\t’ characters between the integers

-

If what the user types in cannot be casted to the expected type, nothing happens. The program continues execution and the variable ends up being uninitialised

-

-

Unformatted line extraction with

std::getlineWhen you want to read an entire line up to and not including the newline character, you should usegetlinerather than directly read fromcin(which always considers space characters ’ ’, ‘\n’, ‘\t’ to be terminating)string msg; std::cin >> msg; // If the user types: hello world, then msg will only be "hello". // If you want to capture the entire line instead, use getline std::getline(cin, msg); -

Common pitfall: when you do formatted execution followed by unformatted extraction, you’ll skip over the unformatted extraction. This is fixed with

std::cin.ignore()Suppose you have:

std::cin >> age; // You type: 10 std::getline(std::cin, name); // You type: AndrewYou are actually typing “10\n” for the first input prompt. The “\n” unfortunately remains in the buffer when we get to the next

getlinecall, which terminates immediately upon seeing the newline, thereby skipping input extract.To solve this, you need to call

std::cin.ignore()to skip over the newline.std::cin >> age; std::cin.ignore(); std::getline(std::cin, name);

File Manipulation (fstream)

The fstream.h header defines ifstream, which you use to open a file in read mode, ofstream, which you use to open a file in write mode, and fstream which you can use to create, read and write to files.

// ═════ Opening a file for reading ═════

ifstream test_file("test.txt");

string line;

while (std::getline(test_file, line)) {

cout << "Read line: " << line << endl;

}

test_file.close();

// ═════ Opening a file for writing (truncating) ═════

ofstream test_file("out.test.txt");

string line;

test_file << "Hello world\n";

test_file.close();

// ═════ Opening a file for writing (appending) ═════

ofstream test_file("out.test.txt", ios::app);

string line;

test_file << "Hello world\n";

test_file.close();// ifstream member methods:

in.eof(); // Returns true if EOF has been reached.String Streams (sstream)

String streams let you treat instances of std::string as stream objects, letting you work with them in the same way that you’d work with cin, cout of file streams.

// You can use `istringstream` anywhere you use `istream`. You can use this to feed strings to something that expects input.

std::istringstream str_in("42 12 24");

int a, b, c;

str_in >> a >> b >> c;

// Similarly, `ostringstream` can substitute for `ostream` instances. You can use this to capture output into a string.

std::ostringstream str_out;

str_out << "Hello world";

std::string extracted = str_out.str();Filesystem

C++17 gives us the std::filesystem API which finally lets us basically do ls on directories and traverse the filesystem, create symbolic links, get file stats, etc.

// Loops through all files in the given directory.

for (const std::filesystem::directory_entry& each_file : std::filesystem::directory_iterator("/usr/bin")) {

cout << each_file.path() << endl;

}Memory

<memory>

<memory> provides two smart pointers: unique_ptr and shared_ptr, for managing objects allocated on the heap.

Use smart pointers whenever you need pointer semantics. The main time you do is when you want to make use of a polymorphic object. You do not need pointer semantics when returning things from a function because that will be handled by copy and move (furthermore, copy elision ensures no unnecessary copies).

unique_ptr

By giving a pointer to unique_ptr, we can have confidence that when that unique_ptr goes out of scope, the object it tracks gets deallocated in the destructor of unique_ptr.

- It’s recommended to use

make_unique<Foo>(...).instead ofunique_ptr<T>(new Foo(...)), mainly so you can completely eliminate the usage of nakednewanddeletes. - Since

unique_ptrrepresents sole ownership, its copy constructor and assignment operation are disabled. You can use move semantics to transfer theunique_ptrfrom one variable to another. - You can pass and return

unique_ptrs in functions (by value).unique_ptr<int> make_foo() { return make_unique<int>(42); }- Wait, why is this allowed when the copy operation is disabled? Basically, it is guaranteed for either copy elision to happen or for

std::moveto be implicitly called on the return value. Either way, the caller ofmake_foois guaranteed sole ownership.“The part of the Standard blessing the RVO goes on to say that if the conditions for the RVO are met, but compilers choose not to perform copy elision, the object being returned must be treated as an rvalue. In effect, the Standard requires that when the RVO is permitted, either copy elision takes place or

std::moveis implicitly applied to local objects being returned.” — Scott Meyers. - Always return smart pointers by value.

- Wait, why is this allowed when the copy operation is disabled? Basically, it is guaranteed for either copy elision to happen or for

“The code using

unique_ptrwill be exactly as efficient as code using the raw pointers correctly.” — Bjarne Stroustrup, A Tour of C++.

shared_ptr

Similar to unique_ptr, but shared_ptrs get copied instead of moved. The object held by shared_ptr is deleted only when no other shared_ptr points at it.

- Prefer

make_sharedover directly constructingshared_ptrand usingnew.

weak_ptr [TODO]

When you assign std::shared_ptr to a variable of type std::weak_ptr, it won’t increment the underlying references count managed by the shared_ptr.

Concurrency

<thread>

void func() {

...

}

int main() {

// When you construct a thread, it starts running the given function in a separate thread immediately.

std::thread my_worker(func);

my_worker.join(); // A synchronous statement that blocks the current thread until `my_worker` has terminated.

return 0;

}-

Simple full example

#include <iostream> #include <thread> using namespace std::literals::chrono_literals; // Allows you to use time literals like `1s`, `1500ms`, etc. static bool finished = false; void DoWork() { while (!finished) { std::cout << "Working...\n"; std::this_thread::sleep_for(1000ms); } } int main() { std::thread worker(DoWork); std::cin.get(); std::cout << "Interrupted!\n"; finished = true; worker.join(); std::cout << "Worker thread has finished execution.\n"; return 0; }

<mutex>

std::mutex is a very simple lockable object used to synchronise access to a resource shared by parallel threads.

lock()

unlock()-

Race condition example and how to solve it with mutexes

#include <iostream> #include <thread> static int count = 0; // This is a shared resource that parallel threads will try to read/write to void IncrementCount() { while (count < 100) { std::cout << "Thread with ID " << std::this_thread::get_id() << " sees count as " << count << "\n"; count++; } return; } int main() { std::thread t1(IncrementCount); std::thread t2(IncrementCount); t1.join(); t2.join(); return 0; }The following is the output of running the program. You can see the lines being printed are also jumbled because

coutis also a ‘resource’ being accessed by both threads. We need to lock access tocountandcout.Thread with ID 140123004860160 sees count as 82 Thread with ID 140123004860160 sees count as 83 Thread with ID 140123013252864 sees count as 85 Thread with ID Thread with ID 140123004860160 sees count as 14012301325286486 sees count as Thread with ID 140123004860160 sees count as 87 Thread with ID 140123004860160 sees count as 88 86Thread with ID Thread with ID 140123013252864 sees count as 90 Thread with ID 140123013252864 sees count as 91Solution:

#include <iostream> #include <thread> #include <mutex> static int count = 0; std::mutex count_mutex; void IncrementCount() { while (count < 100) { count_mutex.lock(); std::cout << "Thread with ID " << std::this_thread::get_id() << " sees count as " << count << "\n"; count++; count_mutex.unlock(); } return; } int main() { std::thread t1(IncrementCount); std::thread t2(IncrementCount); t1.join(); t2.join(); return 0; }Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 82 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 83 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 84 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 85 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 86 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 87 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 88 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 89 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 90 Thread with ID 140367027558144 sees count as 91

<future> [TODO]

async [TODO]

Utilities

<regex>

Note: using raw string literals, , makes writing regex patterns easier because you won’t be confused about backslashes escaping things that you didn’t mean to escape.

#include <regex>

std::regex pattern(R"(.*)");

std::smatch matches; // A container for storing std::string matches (capture groups).

// There are also other containers like std::cmatch for storing

// string literal matches.

// These are all instances of std::match_results and can be

// indexed with the subscript operator [].

matches[i] // Accesses the i-th match. Note: matches[1] accesses the first

// match, matches[2] accesses the second match, and so on.

// ═════ Functions ═════

std::regex_match(haystack, pattern); // Returns true if matched.

std::regex_search(haystack, matches, pattern); // Returns true if matched. Populates the

// std::smatch object with capture group

// matches that you can extract.