Investment

An investment, in macroeconomics, is the act of purchasing new capital goods to bolster productivity.

- Private investment — any investment made by households/businesses. Eg. buying equipment, software, computers, buildings (new dwelling), etc.

- Public investment — any investment made by the government such as infrastructure.

Capital stock — encompasses everything in an economy that enables businesses to generate future sales such as buildings, bridges, literally everything like that.

- Accumulation of capital stock: . The stock at the end of a period is equal to the stock at the start of the period, plus any more investments made over that period, minus the depreciation of the stock at the start.

- Typically, capital goods are durable, meaning they can be consumed multiple times over a longer time period, and can be sold after some use.

The decision of whether a business purchases capital goods (ie. invests) follows the familiar marginal cost-benefit analysis in microeconomics.

- Marginal benefit: value of the marginal product of capital, — value of the marginal product of capital ().

- Marginal cost: user cost of capital, — the cost for holding the capital asset for 1 year, for example. Note that we can resell the capital good since it’s durable.

- A simpler approximation is given as .

- An even further simplification is assuming that changes in the market price is equal to inflation , giving , where .

We will only invest in a capital good if the value of marginal product of capital (margin benefit) equals the user cost of capital (marginal cost), ie. when .

Savings (in Closed Economies)

The amount of savings is the difference between income and consumption.

- Household savings — , where:

- Disposable income can be broken down as: .

- Government transfers is the money you receive from the government directly ‘for free’ (eg. youth allowance).

- Government interest payments is the interest the government pays you for holding government bonds.

- Business retained earnings is the profit that a business won’t pay out as dividends to shareholders.

- Accumulation of wealth: . The change in wealth for a household is given by how much they saved and how much their assets have gained in value.

- Disposable income can be broken down as: .

- Business savings — savings are in the form of retained earnings, ie. the profit that businesses don’t distribute to owners and shareholders as dividends.

- Government savings — also called government budget balance.

National Saving (Supply) and Investment Demand: National saving is the sum of all household, business and government savings: , where business and government savings are exogenous variables, that is, variables whose value is determined by factors outside the current model.

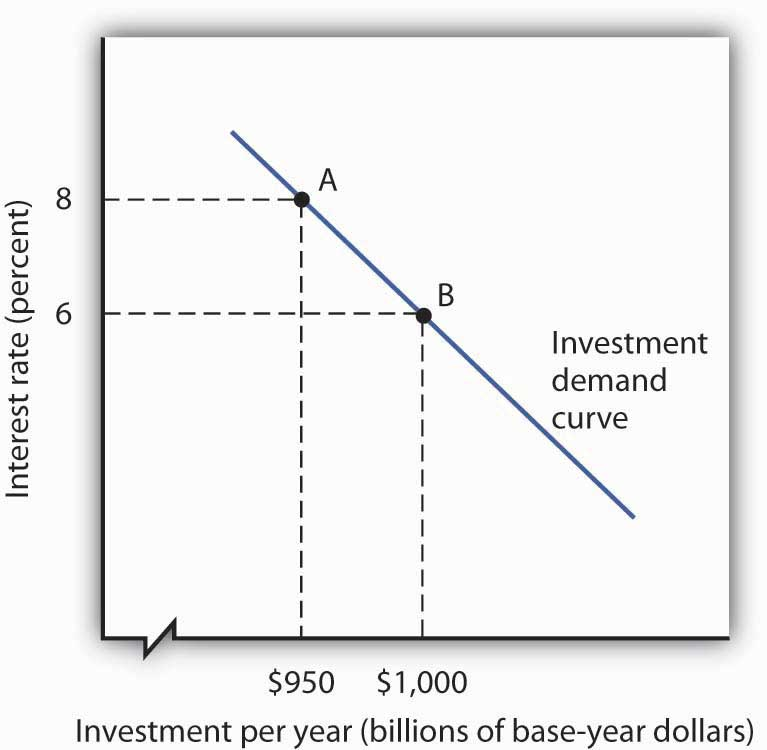

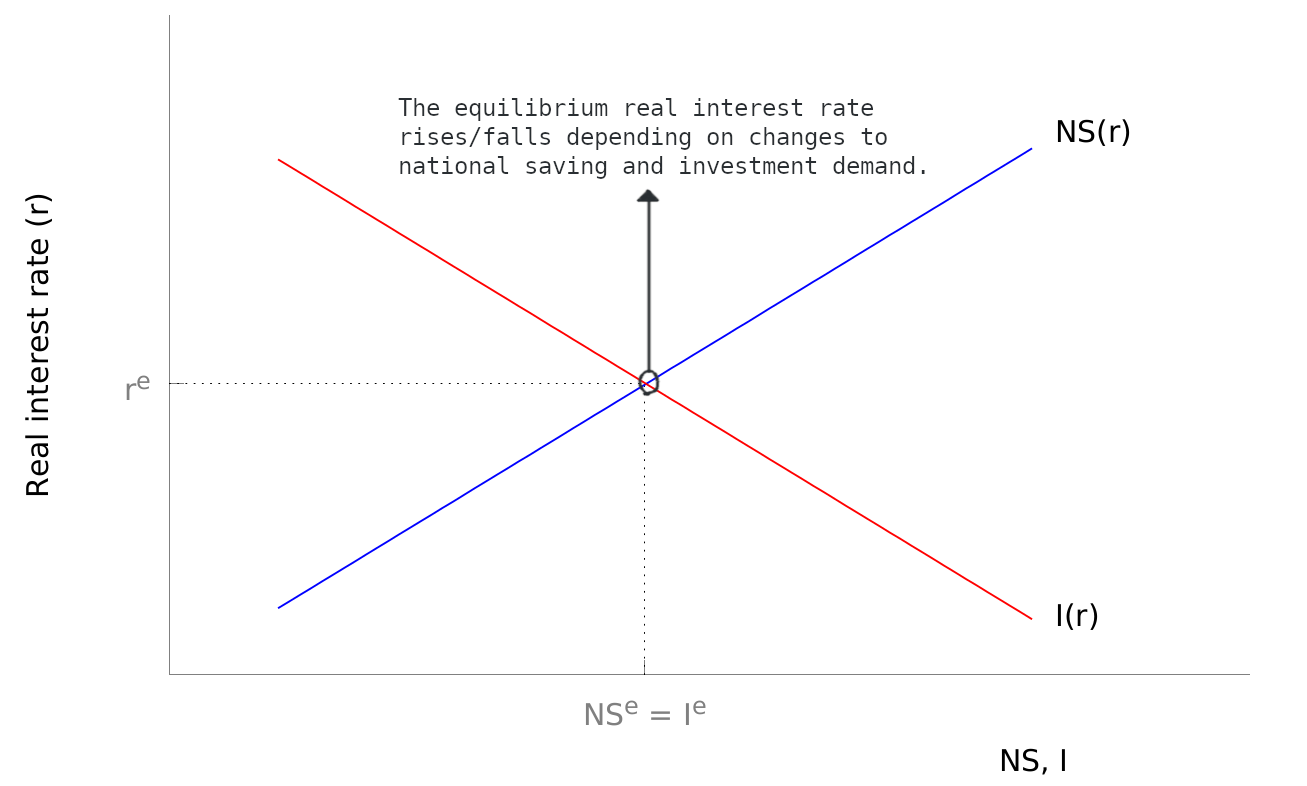

Combining the national saving curve with the investment demand curve, we get an aggregate savings supply and aggregate investment demand graph curve for a closed economy. Remember, both curves depend on the real interest rate . The equilibrium condition is when .

When the RBA sets a higher interest rate, that means higher borrowing costs, so people will tend to save instead of invest. Likewise, setting a lower interest rate encourages households to consume more and businesses to invest more.