C++ is a statically-typed, low-level programming language that supports object-oriented programming. It’s frequently used in any software system that requires resource efficiency such as operating systems, game engines, databases, compilers, etc.

C/C++‘s high performance is attributed to how closely it’s constructs and operations match the hardware.

The ISO C++ standard defines:

- Core language features — data types, loops, etc.

- Standard library components —

vector,map,string, etc.

Also see C++ standard library.

Core

Copy, List and Direct Initialisation

There are a few ways to initialise a variable with a value.

- Copy initialisation: using

=. It implicitly calls a constructor. - List initialisation, also called uniform initialisation: using

{ }. - Direct initialisation: using

( ). Think of the parentheses as being used to directly invoke a specific constructor.

Prefer uniform initialisation over copy initialisation.

```cpp

int b(1); // Direct initialisation.

int a{1}; // List initialisation.

int c = 1; // Copy initialisation.

int d = {1}; // Copy/List initialisation.

```

- List initialisation does not allow narrowing. Try to use list initialisation

{ }more often.int i = 7.8; // Gets floored to 7 int i{7.8}; // Error: narrowing conversion from 'double' to 'int' explicitconstructors are not invokable with copy initialisation.

Designated Initialisers

C++20 introduces a new way to initialise the members of a class/struct:

struct Human {

string name;

int age;

};

int main() {

Human andrew{ .name = "Andrew", .age = 42 };

Human linus{ .name{"Linus"} }; // You can also use list initialisation on the members.

Human ada{ .age = 36, .name = "Ada" }; // Error. You must initialise the fields in the same order as they're declared in the struct/class.

return 0;

}Pointers and References

Pointers and references are really the same thing under the hood, however they have different semantics to the programmer. You can consider references as syntactic sugar for pointers whose main purpose is to help you write cleaner code, compared to if you were to use pointers for the same use case.

Unlike other languages, in C++, arguments are always passed by value by default unless the function signature explicitly says it takes in a pointer or reference. This means functions will entirely copy all the objects you pass in, unless you pass in a pointer/reference.

*and&have different meanings depending on whether they appear in a type declaration (LHS) or whether they appear in an expression that is to be evaluated (RHS).

In a type declaration:

*defines a pointer type.int* arr;&defines a reference variable.int i = 1; int& ref = i;

In an expression:

*is the unary dereference operator that dereferences an address to evaluate to the contents at that address.&is the unary address-of operator that evaluates to the address of a variable.&always expects an lvalue.int i = 1; &i // → Eg. 0x7FFEF2BA1884 &&i // → Illegal operation. &(0x7FFEF2BA1884) doesn't make sense.

Pointers

Pointers are just memory addresses, often to the contents of an object allocated on the heap.

int x = 2;

int y = 3;

int* p = &x;

int* q = &y;

p = q; // p now contains the memory address of y.

nullptr. C++ requires thatNULLis a constant that has value0. Unlike in C,NULLcannot be defined as(void *)nullptrtherefore exists to distinguish between 0 and an actual null for pointer types. People would otherwise mistakenly useNULLand not realise it is just 0

- Note: Stroustrup prefers the pointer declaration style

int* pin C++ andint *pin C.

References

You can think of a reference variable as an alias for another variable. They don’t occupy any memory themselves, once your program is compiled and running.

int x = 2;

int y = 3;

int& r = x;

int& r2 = y;

r = r2; // Remember, you can think of references as aliases. This assignment is basically just `x = y`

- References are useful as function parameters to avoid copying the entire argument. In C++, pass-by-value is the default, although copy elision can happen which nullifies the performance impact of making a copy of an object.

void sort(vector<int>& sequence); // Will sort the given sequence, in-place. - Const references are useful for when you don’t want to modify an argument and just want to read its contents. It prevents the need to make a copy of that argument for the function’s scope. This is really common practice:

void getAverage(const vector<int>& sequence); - References must be initialised and can’t be reassigned afterwards.

- When you return a reference, you are ‘granting the caller access to something that isn’t local to the function’. It is an error to return a reference to a local variable.

new

new is used to instantiate classes and arrays on the heap. All objects allocated with new must have a corresponding delete somewhere.

- You should always prefer stack allocations rather than heap allocations.

- This helps avoid memory leaks because when the variable is allocated for in the stack, its destructor is automatically called when leaving its scope

- It is generally better to avoid having to use

newanddeletein your code, or at least the code that’s using your code shouldn’t have to be responsible for memory management. - Prefer

newanddeleteover C-stylemallocandfree. The reasons are: type safety (sincenewensures instantiated objects are initialised), readability,newthrows an exception on failure whilemallocdoesn’t.

class Human {

public:

Human() {};

};

int main() {

// Creating an object whose memory will be allocated on the heap.

Human* me = new Human();

delete me;

// Creating an array whose memory will be allocated on the heap.

int* A = new int[3];

delete A;

// This array will have its memory allocated on the stack, so no delete operation is necessary.

int B[3];

}delete

There are two delete operators, delete and delete[].

delete— for individual objects. It calls the destructor of that single object.delete[]— for arrays. It calls the destructor on each object.

public:

string* courses;

string* zId;

Student() {

courses = new string[3];

zId = new string("z5258971");

}

~Student() {

delete[] courses; // Deleting an array.

delete zId; // Deleting an individual string.

}

};Type Qualifiers: auto, const, constexpr, static

Auto

When specifying the data type of something as auto, C++ automatically infers the type.

- Use

autofor concision, especially when long generic types are involved. - It’s fine to use copy initialisation if you use

autosince type narrowing won’t be a problem. E.g.auto x = 1. - Always assume that

auto, by itself, will make a copy of the RHS. Useauto&if copying is undesirable (such as when copying large vectors).

Const

The const qualifier makes it ‘impossible’ to assign a new value to a variable after it’s initialised. There is 0 negative performance impact of enforcing const since it’s all done at compile-time. Using const can actually allow the compiler to make optimisations.

Prefer making things const by default. See const correctness for a pitch on why.

constandconstexpr— immutable variables. Declaring and initialising aconstvariable will make the compiler guarantee that its value is never modified, ever.const int i = 1; const auto j {2}; // You can put **const** before pretty much any variable declaration // With **const**, you can assign it a value that is determined during runtime. // With **constexpr**, you can only assign it values known at compile-time constexpr int x = 8; constexpr int x = cube(2); // Error, *unless cube is defined as a [**constexpr function**](https://www.ibm.com/docs/es/xl-c-and-cpp-aix/16.1?topic=functions-constexpr-c11)*

Const Pointers

const int *p; // A pointer to an immutable int.

const int * const q = ...; // An immutable pointer to an immutable int. It must be initialised with a memory address.

int * const r = ...; // An immutable pointer to an int. It must be initisalised with a memory address.If this is hard to read, see the clockwise-spiral rule.

Const References

Typing a variable as a const reference makes it a read-only alias. It’s especially helpful for function parameters.

Prefer typing function parameters as const references. This gives the caller confidence that what they pass in is not modified in any way.

If you don’t want a function to modify a caller’s argument, you have these options:

void foo1(const std::string& s); // Preferred approach.

void foo2(const std::string* s); // A pointer to a const also works.

void foo3(std::string s); // Since pass-by-value is the default, `s` is an independent copy of what the caller passed in.

// If you want a parameter to be modifiable:

void bar1(std::string& s); // This might modify the caller's string directly.

void bar1(std::string* s); // So can this.You can’t have 100% certainty that what you pass as a const reference is unchanged. See this example from isocpp:

Const Methods

Const methods can only read this and never mutate any of its members. The this pointer will essentially become a pointer to const object. To specify a const method, the const qualifier must be placed after the parameter list.

class Student {

public:

// ...

void my_const_func() const {

this->name = "Overridden"; // Compiler error!

}

private:

string name;

};Methods that don’t modify object state should be declared

const. See this const-correctness article

What about making methods return const values, eg.

const Foo bar();? It’s mostly pointless. However, it is not pointless if you’re returning a pointer or reference to something that is const.

Mutable

Declaring a method with const will cause a compiler error to be raised for when that method attempts to change a class variable.

You can add the mutable keyword to allow an exception for what class variables can be modified by const member functions.

class Student {

public:

// ...

void myConstFunction() const {

this->name = "Overridden"; // This is now fine ✓.

}

private:

mutable string name; // Permit `name` to be mutated by const member functions.

};Constexpr

The constexpr type specifier is like const, except the RHS value must be able to be determined at compile-time.

const int a = some_val;

constexpr int b = 42;Constexpr Functions

Constexpr functions are those than can be executed at compile-time, meaning all its state and behaviour is determinable at compile-time.

Static

Static Variables

Inside functions, static variables let you share a value across all calls to that function.

void foo() {

static int a = 42; // All calls to **foo** will see **a = 42**.

... // If **a** changes, then all calls to **foo** will see that change too

}Static function variables are generally considered bad because they represent global state and are therefore much more difficult to reason about*.

Clockwise-Spiral Rule

Clockwise-Spiral Rule is a trick for reading variable types.

- Start at the variable name.

- Follow an outwards clockwise spiral from that variable name to build up a sentence.

Example:

Starting at the name

Starting at the name fp:

fpis a pointer.fpis a pointer to a function (that takes in anintand afloatpointer).fpis a pointer to a function (that takes in anintand afloatpointer) that returns a pointer.fpis a pointer to a function (that takes in anintand afloatpointer) that returns a pointer to a char.

More examples:

int *myVar; // pointer to an int.

int const *myVar; // pointer to a const int.

int * const myVar = ...; // const pointer to an int.

int const * const myVar = ...; // const pointer to a const int.IO

<< — the ‘put to’ operator. In arg1 << arg2, the << operator takes the second argument and writes it into the first.

cout << "Meaning of life: " << 42 << "\n";>> — the ‘get from’ operator. In arg1 >> arg2, the >> operator gets a value from arg1 and assigns it to arg2.

int a, b;

cin >> a >> b;std::endl is a newline that flushes the output buffer, which means it is less performant than "\n".

cout << "Hello" << endl; // Adds a "\n" and flushes the output buffer.

cout << "Hello" << "\n"; // Adds a "\n".

cout << "Hello" << "\n" << flush; // Adds a "\n" and flushes the output buffer.See C++ Standard Library IO for more complex IO operations.

Arrays

The many ways of initialising arrays:

int arr[4]; // [?, ?, ?, ?] – array is full of garbage values, often zeroes.

int arr[4] = { }; // [0, 0, 0, 0] – all elements set to 0.

int arr[4] = { 1, 2, 3, 4 }; // [1, 2, 3, 4].

int arr[4] = { 1 }; // [1, 0, 0, 0] – the rest of array is zeroed.

int arr[] = { 1, 2, 3, 4 }; // Array size can be omitted if it can be inferred from RHS.

int arr[] { 1, 2, 3, 4 }; // You can use uniform initialisation instead of copy initialisation.The size of the array must be able to be determined at compile-time.

Pointers vs. Arrays

What’s the difference between int* array and int array[]? They both can be used to access a sequence of data and are mostly interchangeable.

The main difference is in runtime allocation and resizing: int* array is far more flexible, allowing allocation/deallocation and resizing during runtime, whereas int array[] cannot be resized after declaration.

In general, prefer using declaring true array-types with

[]over pointers-type arrays with*. It’s less error-prone (because you don’t have to worry about dynamic allocation and remembering to free allocated memory) and more readable.

L-Values and R-Values

An lvalue is a memory location that identifies an object. Variables are lvalues.

In C: an lvalue is an expression that can appear on the LHS or RHS of an assignment.

An rvalue is a value stored at some memory address. Rvalues are different from lvalues in that they cannot have a value assigned to it, which means it can’t ever be on the LHS part of an assignment. Literals are typically rvalues.

In C: an rvalue is an expression that can only appear on the RHS of an assignment.

int i = 10; // i is an lvalue, 10 is an rvalue.

int j = i * 2 // i * 2 is an rvalue.

2 = i; // error: expression must be a modifiable lvalue.- Rvalues are important because they enable move semantics in C++. There are many instances in C++ code where it’s not necessary to copy a value or object from one place to another. E.g. when passing arguments into a function or when saving the returned value on the caller’s side. Implementing move semantics, where appropriate, is great for performance because it prevents expensive copies.

Very loosely, Bjarne describes lvalues as “something that can appear on the left-hand side of an assignment” and rvalues as “a value that you can’t assign to.”

L-Value Reference

An lvalue reference uses a single ampersand &, eg. string& s = "..."

- Const lvalue reference types (eg.

const string& s) as a function parameter allow the caller to pass both an l-value or r-value, equivalently.

R-Value Reference

An rvalue reference uses double ampersand &&, eg. string&& s. You’d use this to receive rvalues in functions, like literals and temporary objects. Doing this means you can avoid unnecessarily copying a value that is a ‘throwaway’ on the caller’s side.

- You can define a move constructor and move assignment operator that take in an rvalue reference instead of a const lvalue reference. It’ll behave the same way, but it won’t guarantee the source to be unchanged.

// Takes in an l-value reference which forces the caller to pass in variables.

void GreetLvalue(string &name) {

cout << name << endl;

}

// Takes in an r-value reference which forces the caller to pass in literals

// or temporary objects.

void GreetRvalue(string &&name) {

cout << name << endl;

}

// Const references let the caller pass both lvalues and rvalues alike.

void Greet(const string &name) {

cout << name << endl; // Note: `const string &` will create a temporary variable behind the

} // scenes and then assign it to `name`. This is why you can pass both

// lvalues and rvalues to a const l-value reference like this.

int main() {

string myName = "Tim";

GreetLvalue(myName); // ✓

GreetLvalue("Andrew"); // Error: cannot bind non-const lvalue reference.

GreetRvalue(myName); // Error: cannot bind rvalue reference.

GreetRvalue("Andrew"); // ✓

Greet(myName); // ✓

Greet("Andrew"); // ✓

}Modularity

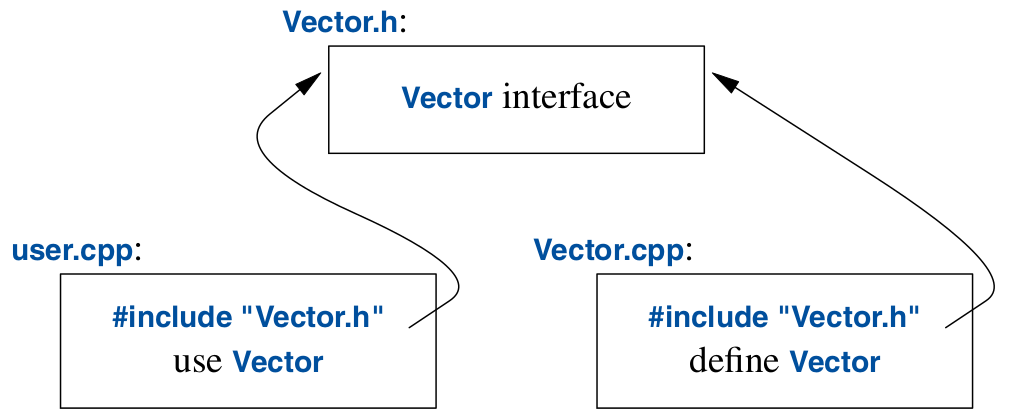

Separate Compilation

C++ supports separate compilation, where code in one file only sees the declarations for the types and functions it uses, not the implementation. This decouples the smaller units comprising a project and minimises compilation time since each unit can be compiled only if they change.

We take advantage of separate compilation by listing out declarations in a header file. Example:

// Vector.h — the header file defining the Vector class and its properties and methods (but without implementation)

class Vector {

public:

Vector(int size);

double& operator[[]];

int size();

private:

double* elements;

int capacity;

};// Vector.cpp — the implementation for Vector.h

#include "Vector.h"

// Implementing the constructor and methods outside of the class definition.

Vector::Vector(int s) :elements{new double[s]}, capacity{s} {}

double& Vector::operator[[]] { return elements[i]; }

int Vector::size() { return capacity; }// user.cpp — the user of Vector.h, who has know idea about how it's implemented.

// It only knows about the declarations inside Vector.h

#include <iostream>

#include "Vector.h"

using namespace std;

int main() {

Vector v(10);

cout << "Vector size: " << v.size() << endl;

}Namespaces

Namespaces define a scope for a set of names. It’s used to organise your project into logical groups and to prevent name collisions when you’re using libraries, for example.

namespace UNSW {

class Student {

public:

string id;

Student(string id) {

this->id = id;

}

};

}

int main() {

UNSW::Student me("z5258971");

std::cout << me.id << "\n";

}- You can do namespace aliases to shorten namespaces. Never do this in header files

namespace testing = ::my::testing::framework; - Use

usingto avoid using a fully qualified name every time.using std::cout; int main() { cout << "Hello world\n"; return 0; } - Any identifier you declare that’s not within a namespace will be implicitly part of the global namespace. Globally scoped identifiers are accessible with

::without specifying a name.int num = 42; namespace Foo { int num = 24; void bar() { std::cout << num; // 24. Picks the closer `Foo::num` over `::num`. std::cout << ::num; // 42. } }

Error Handling

C++ provides the familiar try and catch blocks for error handling. Note that when an exception is thrown, the destructor for the object that threw the exception is called, enabling RAII.

try {

} catch(out_of_range& err) {

} catch(...) {

// All exceptions are caught here when you use `...`

throw; // Use `throw` on its own to re-throw the exception.

}Custom Exceptions

Just inherit from std::exception, implement the const char* what() const throw() method, and a constructor that takes in a string error message.

class MyException : public std::exception {

public:

MyException(const string &message) : message_(message) {}

const char *what() const throw() { return message_.c_str(); }

private:

string message_;

};noexcept

Use noexcept at the end of a function signature to declare that it will never throw an exception. If it does in fact throw an exception, it will just directly std::terminate().

void something_bad() noexcept;Why use it?

- The compiler generates slightly more optimal code since it can assume it doesn’t have to support try-catch control flow.

- For documentation for other developers.

Classes

class Human {

public:

string name;

static string scientific_name;

// Default constructor.

// Having this means that `Human` objects will never be uninitialised.

Human() { ... }

// Destructor. Called when an instance goes out of scope or on exception.

~Human() { ... }

Human(int age, string name) { ... }

private:

int age_;

};

// Non-const static class variables must be initialised outside the class definition.

string Human::scientific_name = "homo sapiens";

int main() {

// **Allocating the object on the heap**

Human* me1 = new Human(20, "Tim");

delete me1;

// **Allocating the object on the stack** (meaning there's not need to call delete)

Human me2(20, "Tim");

Human me3{20, "Tim"}; // An equivalent way of instantiating a class.

Human me4; // Implicitly calls the default constructor.

}- Why do non-const static members have to be initialised outside the class? See this explanation.

Inheritance

Inheritance is done with the syntax class Foo : public Bar. Also see Protected and Private Inheritance.

- Constructors are not inherited by default.

- Child constructors can reference the parent constructors in the member initialiser list following the constructor signature.

- Multiple inheritance is done like this:

class Foo : public Bar, public Baz.

Member Initialiser List and Delegating Constructors

Use a member initialiser list following a constructor signature to initialise class variables and invoke other constructors.

class Foo {

public:

int bar;

string baz;

Foo() : Foo(0, "") {}

Foo(int num) : Foo(num, "") {}

Foo(int num, string str) : bar(num), baz(str) {}

};- ⚠️ This is not to be confused with list initialisation.

- This is not just a shorthand:

- You must initialise const members in the member initialiser list.

- Initialisation is always done before the executing the constructor body.

- Order matters. Initialise members in the same order that they’re declared in the class as a good practice.

Virtual Methods

Virtual methods are methods that have an implementation but which may be redefined later by a child class.

- Pure virtual method — where a function must be defined by a class deriving from this one

```cpp

class Foo {

public:

virtual void Bar() = 0;

}

- ***Abstract class*** — a class that has at least 1 *pure virtual method*. It cannot be instantiated - C++ doesn't have an `abstract` keyword like Java. To make a class abstract, you just define 1 pure virtual method - Concrete class — a class that has no pure virtual functions and can be directly instantiated

overridekeyword — is an optional qualifier that tells programmers that a method is meant to provide a definition for a virtual method from a base class- Any class with virtual functions should always provide a virtual destructor

Object Slicing

When you copy a child object to a variable of the type of the parent, the members specific to the child are ‘sliced off’ so that the resulting object is a valid instance of the parent type.

Parent foo = Child(); // When the child object is copied to a variable of a parent type,

// all its members and overridden methods are - An important consequence of object slicing is that you can no longer call the child class’ overridden methods on when the variable is of the parent type. In the following example, the output is “Something”:

class Parent { public: virtual void do_something() { cout << "Something\n"; } }; class Child : public Parent { public: void do_something() override { cout << "Overridden\n"; } }; int main() { Parent foo = Child(); foo.do_something(); return 0; }- If you used

Parent* foo = new Child();instead, the output would be “Overridden”.

- If you used

Object slicing does not happen in the same way in most other languages, like Java. When you do

Parent foo = new Child()in Java,foo’s overriden methods are still intact and will be called instead of the base method. This is because languages like Java use implicit references to manipulate objects and objects are copied by reference by default, unlike C++.(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

Instantiating Classes

There are several ways of instantiating a class:

void func() {

// Allocated on the stack:

Foo f1; // Implicitly calls the default constructor, Foo().

// In other languages like C#, this would be an uninitialised object.

Foo f2 = Foo(1); // Copy initialisation.

Foo f3 = 1; // Also copy initialisation.

Foo f4(1); // Direct initialisation.

Foo f5{1}; // List initialisation (generally preferred because it avoids implicit type

// conversions and avoids creating unnecessary temporary objects).

Foo f6 = {1}; // Also copy initialisation, but with an initialiser list.

Foo f7(); // You'd think this is calling the default constructor, but it's not.

// See 'most vexing parse'. Use `Foo f7;` instead to call the default ctor.

// Manually allocated on the heap (avoid when posssible):

Foo* f8 = new Foo();

delete f8;

}Note that when using brace initialisation, the constructor that takes in a std::initializer_list will be preferred for invocation.

class Foo {

public:

Foo(initializer_list<int>) {

cout << "Initialiser list constructor called.\n";

}

Foo(const int&) {

cout << "Normal constructor called.\n";

}

};

int main() {

Foo b(42); // Normal constructor called.

Foo c{42}; // Initialiser list constructor called.

return 0;

}General Guidelines*:

- Use

=if the (single) value you are initialising with is intended to be the exact value of the object.- Prefer using

=when assigning toautovariables. - Prefer when initialising variables with primitive types (eg. int, bool, float, etc.).

- Prefer using

- Use

{ }if the values you are initialising with are a list of values to be stored in the object (like the elements of a vector/array, or real/imaginary part of a complex number).- Prefer using { } in the majority of cases because it can be used in every context and is less error-prone than the alternatives.

- Use

( )if the values you are initialising with are not values to be stored, but describe the intended value/state of the object, use parentheses.- Essentially, if the intent is to call a particular constructor, then use parentheses

( ). - E.g. good example with

vector:vector<int> **v(10)**; // Empty vector of 10 elements cout << v.size() << endl; // Prints **10** vector<int> **u{1, 2, 3}**; // Vector with elements 1, 2, 3 cout << u.size() << endl; // Prints **3**

- Essentially, if the intent is to call a particular constructor, then use parentheses

- In general, prefer allocating on the stack rather than the heap, unless you need the object to persist after the function terminates.

- You’d have to use

unique_ptrif you don’t want to memory-manage withnewanddelete.- Allocating on the heap is less performant than allocating on the stack. Stack allocation is faster because the access pattern makes it trivial to allocate and deallocate memory from it (a pointer/integer is simply incremented or decremented), while the heap has much more complex bookkeeping involved in memory allocation/deallocation.

- Very large objects should be allocated on the heap to prevent stack overflow (the heap is larger than the stack).

- You’d have to use

- Note: In Java/C#, you can’t allocate objects on the stack, they’d all be allocated on the heap. You could use a

structinstead

Const Objects

const objects prevents its fields being modified. You can only call its const methods.

class Student {

public:

string name;

Student() {

this->name = "Andrew";

}

void setName(string name) {

this->name = name;

}

};

int main() {

const Student s;

s.name = "Taylor"; // ✘ not fine because this modifies a class variable.

s.setName("Taylor"); // ✘ not fine because this calls a non-const method.

}Note the differences between

const Foo foo = ...;in C++ vs.const foo = ...in JavaScript/TypeScript. In JavaScript, you can still mutate the fields freely by default, you just can’t reassignfooto point to a different object.

Final Methods

Postfixing a method signature with the final keyword will make it so that it cannot be overridden by a deriving class.

- Why not just declare a method without the

virtualmodifier? Wouldn’t that prevent overriding? See why final exists.

class FooParent {

public:

virtual void Info() = 0;

};

class Foo : public FooParent {

public:

void Info() override final {}

};

class FooChild : public Foo {

public:

void Info() override {} // Error: cannot override final funtion

};Explicit Methods

You can prefix explicit in front of a constructor or method signature to prevent implicit type conversions.

- It’s good practice to make constructors

explicitby default, unless an implicit conversion makes sense semantically. Source.- Why doesn’t the language make constructors explicit by default? Because people thought it was cleaner and now it’s irreversible because people want backward compatibility (source).

class MyVector {

public:

int size;

explicit MyVector(int num) : size(num) {}

};

int main() {

MyVector v = 2; // Without an explicit constructor, this actually invokes `MyVector(2)`.

} // When you define `explicit MyVector(int num)`, this call would cause an error.Friend Classes

Inside your class body, you can declare a class as a friend which grants them full access to all your class’ members, including private ones. Just remember the inappropriate but memorable phrase: “friends can access your privates”.

A class can declare who their friends are in their body. Friends are then able to access everything within that class, including private members.

- You can only declare who’s allowed to access you, not who you can have access to. Like in real life, you can’t grant yourself access to someone else’s privates, but you can grant others access to yours 😏.

- You can declare other classes or specific functions as your friends.

class Baby {

public:

Baby(const string& name) {}

// Methods of `Mother` will be able to see everything in `Baby`.

friend class Mother;

private:

string name;

};

class Mother {

public:

Mother(const string& babyName) : baby(babyName) {}

void rename_baby(const string& new_name) {

// This is only possible because of `friend class Mother`.

baby.name = new_name;

}

private:

Baby baby;

};

int main() {

Mother mum("Andrew");

mum.RenameBaby("Andy");

}When to use friend classes?

- When you want to write white-box unit tests, you can declare the unit test class as a friend. It’s good for unit testing private methods which you don’t want to expose to anyone other than the unit testing class.

- Caveat: it’s debatable whether it’s good practice to test private methods. Testing a public method should indirectly test a private method anyway.

Use friend classes sparingly. If you’re in a situation where you want to use a friend class, it’s a red flag, design-wise.

Deleted Functions

Just like how you can use = 0 to declare a function to be a pure virtual function, you can use = delete to declare a function to be a deleted function, where it can no longer be invoked. This is mostly used to suppress operations and constructors to prevent misuse.

class A {

public:

A() = default;

// Deleted copy constructor.

A(const A& other) = delete;

// Deleted assignment operator.

A &operator=(const A& other) = delete;

};

int main() {

A a1;

A a2 = a1; // error, copy constructor is deleted.

a1 = a2; // error, assignment operator is deleted.

return 0;

}Defaulted Functions

Like deleted functions, you can postfix a constructor or method signature with = default to make the compiler supply a default implementation.

class A {

public:

A() = default;

// Default copy constructor.

A(const A &other) = default;

// Default assignment.

A &operator=(const A &other) = default;

// Default destructor.

~A() = default;

};RAII

The technique of acquiring resources in the constructor and then freeing them in the destructor is called RAII (Resource Acquisition is Initialisation). The idea is about coupling the use of a resource to the lifetime of an object so that when it goes out of scope, or when it throws an exception, the resources it held are guaranteed to be released. Always design classes with RAII in mind.

class ResourceHolder {

public:

ResourceHolder() {

arr = new int[12];

}

~ResourceHolder() {

delete[] arr;

}

private:

int* arr;

};- This works well for mutexes where you can acquire the lock in the constructor and unlock it in the destructor.

- RAII is implemented religiously in standard library resources such as threads, files, data structures, etc.

Operator Overloading

You can define operations on classes by overloading operators like +, +=, ==, etc.

class Coordinate {

public:

int x;

int y;

Coordinate operator+(const Coordinate &other) {

return {.x = this->x + other.x, .y = this->y + other.y};

}

};

int main() {

Coordinate foo{42, 24};

Coordinate bar{2, 2};

Coordinate result = foo + bar;

cout << "Coordinate: " << result.x << ", " << result.y << endl;

return 0;

}- Operator overloading is just a type of static polymorphism. Operators are just functions. When compiled, expressions with operators are just converted to equivalent function calls. E.g.

a += bbecomesoperator+=(a, b). - Operator overloading also exists in C#, Java, Python, etc.

- Make sure the copy constructor/assignment is implemented such that logical equivalences hold. E.g.

a != bshould be the same as!(a == b), etc.

Copy Constructor and Operation

A copy constructor is a constructor that takes in a (typically const) reference to an instance of the same class. A copy assignment operator overload also takes in a (typically const) reference to an instance of the same class and returns a reference to an instance of the same class.

class Foo {

public:

// Copy constructor.

Foo(const Foo& other) { ... }

// Copy assignment operator.

Foo& operator=(const Foo& other) { ... }

};The copy constructor is invoked implicitly in a number of situations:

- Passing by value to a function (the function creates its own copy for local use).

- Returning a value will create a copy for the caller (this can be very inefficient, which is why optimisations like copy elision and move semantics exists).

- Copy initialisation:

Foo foo; Foo bar; Foo baz = foo; // Implicitly calls the copy constructor. baz = bar; // Calls copy assignment operator, not the copy constructor.

If you don’t implement the copy constructor yourself, the compiler generates a default copy constructor that performs a simple memberwise copy to form a new object. Often, this default copy constructor is acceptable. For sophisticated concrete types and abstract types, the default implementation should be deleted or manually implemented.

-

An example of when default copy could be bad: when your class holds a pointer to a resource, a memberwise copy would copy the pointer over to the new object. Now both objects would affect the same resource.

E.g. suppose we have a crappy

Vectorimplementation that uses the default copy constructor and copy assignment operator.Vectormanages a pointer to an underlying array. When you just do a memberwise copy, you only copy over the pointer to the underlying array, not the underlying array itself.

Move Constructor and Operation

A move constructor is a constructor that takes in an rvalue reference to an instance of the same class. A move assignment operator overload takes in an rvalue reference (to an instance of the same class) and returns a reference to the same class.

class Foo {

public:

// Move constructor.

Foo(Foo&& other) { ... }

// Move assignment operator.

Foo& operator=(Foo&& other) { ... }

};Suppose you have a function that returns a large object (e.g. a big matrix) and you want to avoid copying it to the caller, which would be very wasteful of clock cycles. Since you can’t return a reference to a local variable, and it is a bad idea to resort to the C-style returning of a pointer to a new object that the caller has to memory-manage, the best option is to use a move constructor.

- Move constructors are implemented to ‘steal’ over the resources held by the given instance (hence why we don’t take in a

constrvalue reference). This means transferring over things like underlying data structures, file handles, etc.

class Foo {

public:

Foo(initializer_list<int> vals) {

arr_ = new int[vals.size()];

size_ = vals.size();

int i = 0;

for (const int& val : vals) arr_[i++] = val;

}

// Move constructor.

Foo(Foo&& other) {

// Steal the given Foo's members/resources.

arr_ = other.arr_;

size_ = other.size_;

other.arr_ = nullptr;

other.size_ = 0;

}

// Move assignment operator.

Foo& operator=(Foo&& other) {

if (this == &other) return *this;

arr_ = other.arr_;

size_ = other.size_;

other.arr_ = nullptr;

other.size_ = 0;

return *this;

}

void print_vals() {

cout << "Values: ";

for (int i = 0; i < size_; ++i) cout << arr_[i] << " ";

cout << "\n";

}

private:

int* arr_;

int size_;

};

int main() {

Foo foo{2, 4, 8};

Foo bar{};

foo.print_vals();

bar.print_vals();

bar = std::move(foo);

foo.print_vals();

bar.print_vals();

return 0;

}std::move

Suppose you have a class Foo that implements a move constructor: Foo(Foo&& other). To invoke this, you’d do something like:

Foo foo;

Foo bar((Foo&&)foo); // Invoke the move constructor.Since this is ugly and doesn’t work for auto inferred types, we have std::move instead.

Foo foo;

Foo bar(std::move(foo)); // Read this like: "moving foo's contents to bar."Once you’ve used move(foo), you mustn’t use foo again. Because it’s error prone, Bjarne recommends to use it sparingly and only when the performance improvements justify it.

std::movedoesn’t actually move anything, which is a bit misleading. It just converts an lvalue to rvalue reference so as to invoke the move constructor. It has zero side effects and behaves very much like a typecast. The actual ‘moving’ itself is done by the move constructor.A less mislead name for

std::movewould have beenrvalue_cast, according to Bjarne.

std::move(foo)basically says “you are now allowed to steal resources fromfoo”.

Templates

Templates in C++ are a code generation system that lets you specify a general implementation of a class or function and then generate specialised instances of that template for different types, on demand.

- Templates provides everything offered by generics in languages like Java, plus more.

- Since templates are purely a compile-time feature, there is no real difference between template-generated code and equivalent handwritten code.

To make a class or function a template, just prefix the definition with the template keyword followed by a list of type parameters: template <typename A, typename B, ...>.

- Read

template <typename T>as “for all types T, …” - You can also use the

classkeyword instead oftypename. They’re interchangeable.// These two are equivalent: template <typename T> template <class T> - Templates can take in value arguments as well as type arguments:

template <typename T, int N> T* make_array() { return new T[N]; } int main() { auto arr = make_array<int, 12>(); delete arr; return 0; }

Templates vs. Generics

Templates are massively different from generics in other OOP languages like Java.

In Java, generics are mainly syntactic sugar that help programmers avoid boilerplate code. In C++, templates are a code generation system that enables generic programming and more. Some main differences:

Think of C++‘s templates as very sophisticated preprocessor commands. It’s used to generate type-safe code. In Java’s generic system, type erasure is used, resulting in a single implementation of the generic class/function rather than many specialised instances of a template like in C++.

Function Templates

Function templates are a generalised algorithm that the compiler can generate copies of for usage with specific types.

template <typename T, typename U>

void foo(T t, U u) {

// ...

}Tis a type argument. Its scope is limited to the function signature and body.- Strictly speaking, a function template is not really a function. It’s a generalisation of an algorithm that is used as a tool by the compiler for generating similar but independent functions.

- The act of generating a function from a function template by the compiler is called template instantiation

A generic swap function:

template <typename T> // Start of T's scope

void swap(T& a, T& b) {

T tmp = a;

a = b;

b = tmp;

} // End of T's scope- When you invoke

swap<int>(i, j), the compiler will instantiate a function with signaturevoid swap<int>(int& a, int& b)for you by plugging in the types into the template function you defined.- Template instantiation is done on-demand when you compile.

- The compiler is smart enough to avoid instantiating duplicate functions.

Class Templates

Basically function templates, but with classes.

template <typename Item>

class Stack {

public:

void push(Item i);

void show();

private:

vector<Item> vec_;

};

// When implementing methods outside of the class, you must fully qualify

// the method name with the prefix `MyContainer<T>::`.

//

// Anything following `::` will be within the class' scope, meaning that

// specifying <T> becomes optional again — because T is known in the class

// body.

template <typename Item>

void Stack<Item>::push(Item i) {

vec_.push_back(i);

}

template <typename Item>

void Stack<Item>::show() {

for (const Item& item : vec_)

cout << item << " ";

cout << "\n";

}

int main() {

Stack<int> nums;

nums.push(42);

nums.push(24);

nums.show();

Stack<string> strs;

strs.push("Hello");

strs.push("World");

strs.show();

return 0;

}- Note: when within the scope of the class body, you can use

MyContainerandMyContainer<T>interchangeably. Essentially, you can consider<T>optional inside the class body. However, when outside the class scope (i.e. before the::), you have to fully qualify the name withMyContainer<T>::- Once you specify the

::inMyContainer<T>::, you can imagine that you’re basically re-entering the class scope, and then everything you could access within the class become available again. (sourced from CppCon)

(sourced from CppCon)

- Once you specify the

Aliases

You can use using to create type aliases for template types.

template <typename T>

using MyMap = unordered_map<T, string>;

int main() {

MyMap<string> map;

map.insert(make_pair("Hello", "world"));

map.insert(make_pair("Goodbye", "world"));

return 0;

}Concepts [TODO]

Concepts are predicates that are used to apply constraints to the type arguments you pass to a template function or class. The main reason to use concepts is to get the compiler to be better at preventing misuage.

- This is from C++20. Prior to C++20, you’d rely on [[Knowledge/Engineering/Languages/C++#Type Traits [TODO]|type traits]] with

static_asserts, or simply trusting programmers to follow documentation on how to use a template correctly. - Useful concepts are provided in the standard

<concepts>header.

TODO: notes on concept-based overloading, defining concepts.

template <...>

requires

// The equivalent and less verbose way to use concepts without requirements clauses:

template <...>- You can overload template functions: depending on the type arguments, run a different generic algorithm.

template <typename T, typename U = T>

concept EqualityComparable =

requires (T a, U b) {

{ a == b } -> bool;

{ a != b } -> bool;

{ b == a } -> bool;

{ b != a } -> bool;

}

// ...

static_assert(EqualityComparable<int, double>);

static_assert(EqualityComparable<int>);

static_assert(EqualityComparable<char>);

static_assert(EqualityComparable<char, string>); // Fails.Type Traits [TODO]

Deduction Guides [TODO]

This is for aiding type inference.

Functors

Functors, or function objects, are instances of a class that implements the function call operator method, operator(), which means that they can invoked as if they were functions themselves. Functors are highly customisable, reusable, stateful functions.

class DrinkingLaw {

public:

DrinkingLaw(int required_age) : required_age_(required_age) {}

// Implementing this method is what makes this class a functor

bool operator()(int age) {

return age >= required_age_;

}

private:

int required_age_;

};

int main() {

DrinkingLaw canDrink(18);

cout << "I can drink: "

<< (canDrink(21) ? "Yup" : "Nope")

<< endl;

}Lambda Functions

You can think of lambda functions as syntactic sugar for inline, anonymous functors.

[_] (params) -> RetType { // You can omit the return type if it can be inferred.

// Function body

}You can use the capture clause (the [] of the expression) to access variables from the outer scope.

[&foo, bar]— capturesfooby reference andbarby value.[&]— capture all variables by reference.[&, foo]— capture all variables by reference apart fromfoo, which is captured by value.

[=]— capture all variables by value.[=, &foo]— capture all variables by value apart fromfoo, which is captured by reference.

A classic use of lambda functions is passing it as the comparator function to std::sort to determine whether one element comes before another.

int main() {

vector<int> v{2, 4, 8};

std::sort(v.begin(), v.end(), [] (int a, int b) {

return a > b;

});

for (int val : v) cout << val << " ";

cout << "\n";

return 0;

}Enums

In addition to structs and classes, you can also use enums to declare new data types. Enums are used to represent small sets of integer values in a readable way. There are two kinds of enums in C++, plain enums and enum classes (which are preferred over plain enums because of their type safety).

Plain Enum

Declared with just enum. The enum’s values can be implicitly converted to integers

enum Mood { happy, sad, nihilistic };

int main() {

Mood currMood = Mood::happy;

int val = currMood; // No error, the Mood value is implicitly converted to an integer type.

}Enum Class

When you declare an enum with enum class, it is strongly typed such that you won’t be able to assign an enum value to an integer variable or to another enum type. It reduces the number of ‘surprises’ which is why it’s preferred

enum class Mood { happy, sad, nihilistic };

int main() {

Mood currMood = Mood::happy;

int val = currMood; // Error, Mood::happy is not an int.

}Initialiser List

std::initializer_list is a special class whose objects are used to pass around a sequence of data using curly braces {} in a readable, intuitive way.

std::initializer_listis an iterable.- For some reason, you cannot subscript an instance of

std::initializer_listlike you would a vector or array (SO discussion).

The compiler automatically converts { ... } to an instantiation of std::initializer_list in these situations:

{}is used to construct a new object:Person person{"Tim", "Zhang"}This will call the constructor of signaturePerson(std::initializer_list<string> l) {...}if it exists. If such a constructor doesn’t exist, it will look forPerson(string firstName, string lastName) { ... }. So basically, it prefers invoking constructors that take instd::initializer_listbut it will silently fall back to direct invocation if that fails.- Constructors taking only one argument of this type are a special kind of constructor, called initialiser-list constructor.

struct Foo { Foo(int,int) { ... }; Foo(initializer_list<int>) { ... }; }; Foo foo {10,20}; // Calls the initialiser-list constructor. Calls `Foo(int, int)` if it doesn't exist. Foo bar (10,20); // Calls `Foo(int, int)`.{}is used on the RHS of an assignment:vector<int> vec = { 1, 2, 4 };{}is bound toauto. E.g.for (auto i : { 2, 5, 7 }) // `std::initializer_list` is an iterable. cout << i << endl;

Interesting questions:

- It’s not possible to implement your own

std::initializer_list. It’s coupled to the language standard and the logic of the compiler, which you can’t recreate through your own class. - Why isn’t

std::initializer_listbuilt-in?

Iterators

An iterator is an object that points to a specific item in a container. It has methods and operations for iterating over a container.

- To support range-based for loops, your class has to implement the

begin()andend()methods and make them return an iterator.

std::vector<int> values = {1, 2, 3};

for (std::vector<int>::iterator it = values.begin(); it != values.end(); it++)

cout << *it << endl;

// Syntactic sugar for the above:

for (int value : values)

cout << value << endl;end()isn’t the last element, it points one position beyond the last element.- There is also:

const_iteratorfor read-only iteration.reverse_iteratorfor reverse iteration. Use it withrbeginandrend

Iterator Categories

There are different types of iterators in C++, in order to least functionality to richest functionality:

- Input iterator — you can only access the container in a single forward pass.

- Output iterator — you can only assign values to the container in a single forward pass.

- Forward iterator — combines input and output iterators.

- Bidirectional iterator — forward iterator that can also go back.

- Random access iterator — you can move the iterator anywhere, not just forward and back.

They form a hierarchy where forward iterators contain all the functionality of input and output iterators, bidirectional contains all of forward, and random-access contains all of bidirectional:

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

The STL containers support different iterator categories:

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

(sourced from GeeksForGeeks)

Random C++ Features

Other important C++ details.

Structured Bindings

You can unpack values in C++17, similar to how you destructure objects in JavaScript. It’s just syntactic sugar.

struct Coordinate {

int x;

int y;

};

int main() {

Coordinate point{2, 4};

auto [foo, bar] = point; // foo == 2, bar == 4

return 0;

}- JavaScript calls this destructuring, Python calls this unpacking, C# calls this deconstructing.

- Unfortunately, you have to specify as many identifiers as there are things to unpack.

- Ranged for-loop:

map<string, int> m; m.insert(pair<string, int>("Hello", 42)); m.insert(pair<string, int>("World", 24)); for (const auto& [key, val] : m) { cout << "Key: " << key << ", val: " << val << endl; } - Tuple destructuring:

tuple<int, bool, double> tup(1, false, 3.14); auto [x, y, z] = tup;

Using

There are a few different ways the using keyword is used:

- Type aliasing (alternative to C-style

typedef). It’s generally more preferred to useusingover C-styletypedef. It also supports a little more extra functionality that is not available withtypedef, specifically for templates. Source// These two are (mostly) equivalent: using Age = unsigned int; typedef unsigned int Age;typedefis locally scoped.usingmakes the type alias available in the whole translation unit.

- Make an identifier from a namespace available in the current namespace.

using std::cout; using std::cin; - Make all identifiers from a namespace available in the current namespace.

using namespace std;- Avoid this as much as possible in large projects. It pollutes your namespace with lots of new identifiers.

using namespaceshould never be used in header files because it forces the consumer of the header file to also bring in all those identifiers into their namespaces

- Lifting a parent class’ members into the current scope.

- Can be used to inherit constructors:

class D : public C { public: using C::C; // Inherits all constructors from C. void NewMethod(); };

Copy Elision

By default, when you pass an object to a function, that object is copied over (pass-by-value). When it doesn’t affect program behaviour, the compiler can move the object rather than making a full copy of it. This compiler optimisation can also happen when returning an object, throwing an exception, etc.

string foo() {

string str = "Hello, world!";

return str; // copy elision occurs here

}

int main() {

string s = foo();

}- Note: in English/linguistics, to elide means to merge and therefore omit something in language. E.g. “dunno” == “don’t know”.

Copy elision is not enforced in the C++ standard, so don’t write code assuming this optimisation will happen.

Return Type Deduction

In C++14, you can infer the return type of function whose return type is left as auto.

auto multiply(int a, int b) { return a * b; }In A Tour of C++, Bjarne says to not overuse return type deductions.

Initialiser List

You can make a constructor or method take in an std::initializer_list to let the caller directly pass in a curly brace list like {1, 2, 3, 4} as an argument.

class Foo {

public:

vector<int> values;

Foo(const std::initializer_list<int>& elems) {

for (const int &elem : elems)

values.push_back(elem);

}

void foo(const std::initializer_list<int>& elems) {

for (const int& elem : elems)

cout << "Elem: " << elem << endl;

}

};

int main() {

Foo foo = {1, 2, 4, 8};

foo.foo({ 1, 2, 3 });

return 0;

}When the compiler sees something like {1, 2, 3, 4}, it will convert it to an instance of std::initializer_list (if used in a context like above).

Casting [TODO]

static_cast— casts from one type to another. It does not check what you’re doing makes sense, so avoid using it often.dynamic_cast— casts pointer/reference types. Useful for runtime type-checking of objects. E.g. you can convert an instance of a parent class into an instance of a child class.class Parent { public: virtual ~Parent() {} }; class Child : public Parent {}; int main() { Parent* foo = new Child(); if (Child* child = dynamic_cast<Child*>(foo)) cout << "foo is a child.\n"; return 0; }- Sometimes you have to use this, but do so sparingly.

“If we can avoid using type information, we can write simpler and more efficient code, but occasionally type information is lost and must be recovered. This typically happens when we pass an object to some system that accepts an interface specified by a base class. When that system later passes the object back to us, we might have to recover the original type.” — Bjarne Stroustrup, A Tour of C++.

- Sometimes you have to use this, but do so sparingly.

reinterpret_cast— treating an object as a raw sequence of bytes.const_cast— casts away ‘constness’.(type) value— C-style typecasting. This is the least preferred way since it’s unconstrained.

Inline Functions

inline functions: when you want a function to be compiled such that the code is put directly where it’s called instead of going through the overhead of entering a new function context, make that function inline.

I.e. if you want the machine code to not have function calls to this function, put inline before the function signature. This tells the compiler to place a copy of the function’s code at each point where the function is called at compile time.

inline void foo();- Inlining functions offers a marginal performance improvement (usually) because you avoid allocating a new stack frame that’s usually associated with making a function call.

- This performance improvement is done at the cost of a marginally bigger executable size since the code is now duplicated across potentially many places. Smaller functions are usually better candidates for inlining.

- Why not make everything inline?

if-statement With Initialiser

In C++17, you can declare variables inside if statements and follow it up with a condition: if (init; condition) { ... }.

vector<int> vec = { 1, 2, 3 };

if (int size = vec.size())

cout << "Vector size is not 0" << endl;

if (int size = vec.size(); size > 2)

cout << "Vector size is > 2" << endl;Noexcept Conditions

noexcept(false): it’s possible to usenoexcept(false)in function signatures to say that ‘this function throws no exceptions (but it actually might, lol)‘. Just avoid using it.noexcept(true)andnoexceptare completely equivalent.throw(): in older C++, you can putthrow()at the end of a function signature to say that the function never throws exceptions, for example:void something_bad() throw(). It’s been deprecated bynoexceptin C++11, which is preferred overthrow(), so you’d do:void something_bad() noexceptinstead.

Aggregates

Aggregates are either arrays or structs/classes that you didn’t define constructors, private/protected instance variables or virtual methods for. When those conditions are met, that class is an aggregate type and can be initialised with {}.

- The order that you declare the fields matter.

Even though they both use

{}, aggregate initialisation is different from list initialisation!

PODs

PODs (Plain Old Data) are a kind of aggregate type that do not overload operator=, have no destructor, and there are no non-static members that are: non-POD classes, arrays of non-POD classes, or references. Learn more.

Put simply, PODs are just simple data, or simple data containers, hence the name ‘plain old data’.

- They’re very similar to structs in C.

- Because they’re very simple, using PODs can offer performance advantages because the compiler no longer needs to set up the same abstractions necessary for normal classes to work, letting them generate more efficient code.

- Many built-in types are PODs, such as

int,double,enums, etc.

Protected and Private Inheritance

Protected and private inheritance are specific to C++. Other languages usually won’t have this.

Just default to using public inheritance (

: public) if you want to represent an is-a relationship. Use protected and private inheritance sparingly.

class Parent {

public:

int a;

protected:

int b;

private:

int c;

};

class PublicChild : public Parent {

// a is public.

// b is protected.

// c is inaccessible here.

};

class ProtectedChild : protected Parent {

// a is protected.

// b is protected.

// c is inaccessible here.

};

class PrivateChild : private Parent {

// a is private.

// b is private.

// c is inaccessible here.

};- Protected inheritance makes all public members inherited from the parent protected.

- Private inheritance makes all public and protected members inherited from the parent private. Private inheritance basically hides the inheritance from the rest of the world.

Class Prototypes

Class prototypes are just like function prototypes. You can declare all your classes upfront and then use them wherever you want throughout the code.

// Declare classes.

class A;

class B;

// Define classes later (any order is okay).

class B { ... };

class A { ... };User-Defined Literals

It’s possible to define custom literals that improve readability. E.g. <chrono> makes it possible to write: 24h, 42min, etc. directly.

Example:

constexpr int operator""min(unsigned long long arg) {

return 60 * arg;

}

int main() {

cout << "Seconds: " << 42min << "\n";

return 0;

}thread_local

There is a thread_local keyword in C++. When a variable is declared with thread_local, it is brought into existence when the thread starts and deallocated when the thread ends. In that sense, the thread sees that variable as a static variable since it exists throughout its lifetime.

thread_local int myInt = ...;Unnamed Scopes

Usually, we use {} to define scopes for functions, classes, if-blocks, for-loops, etc., but you can also just use them directly in code to create a restricted scope.

void foo() {

cout << "Hello\n";

{ // Start of an unnamed scope.

// A smaller scope containing some statements

}

return;

}- Doing this within a function is useful when you want a destructor to be called as soon as possible. E.g. often when dealing with mutexes, you’d want to acquire and release a lock as soon as possible.

Union

A union is data structure like a class or struct, except all its members share the same memory address, meaning it can only hold 1 value for one member at a time. The implication is that a union can only hold one value at a time, and its total allocated memory is equal to .

- It’s mainly used when you really need to conserve memory.

- They’re mostly useless in C++ but more useful in C.

union Numeric {

short sVal;

int iVal;

double dVal;

};

int main() {

cout << "Unions" << endl;

Numeric num = { 42 };

cout << num.sVal << endl; // Prints 42.

cout << num.iVal << endl; // Prints 42.

cout << num.dVal << endl; // Interprets the bits of 42 using floating point representation (IEEE 754).

}Compile-Time If [TODO]

if constexpr() { ... }. C++17.

Volatile [TODO]

Extern

From what I understand, extern int foo is basically saying “trust me compiler, there’s an int called foo that is defined somewhere.”

// main.cc

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// `foo` exists, but its value is defined in some other file. Trust me, compiler.

extern int foo;

std::cout << foo << "\n";

return 0;

}

// foo.cc — there is literally just this one line in this file.

int foo = 42; Compiling the above with g++ -o main main.cc foo.cc and it just works.

Fold Expressions [TODO]

Appendix:

All the notes under this section are meant to be topics or details you don’t need to care much about to program effectively with C++.

C++ Compilation [TODO]

Compilation of C++ programs follow 3 steps:

- Preprocessing

Preprocessor directives like

#include,#define,#if, etc. transforms the code before any compilation happens. At the end of this step, a pure C++ file is produced. - Compilation The compiler (eg. g++, the GNU C++ compiler) takes in pure C++ source code and produces an object file. This step doesn’t produce anyting that the user can actually run — it just produces the machine language instructions.

- Linking Takes object files and produces a library or executable file that your OS can use.

Commenting

The advice here is sourced from Google’s C++ style guide.

File Comments

File comments are preferred but not always necessary. Function and class documentation, on the other hand, must be present with exceptions only for trivial cases.

- Start with licence boilerplate, then broadly describe what abstractions are introduced by the file.

- Don’t duplicate comments across a class’

.hand.ccfile. Example

// Copyright 2008, Google Inc.

// All rights reserved.

//

// Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without

// modification, are permitted

// ... and so on

//

// Google C++ Testing and Mocking Framework (Google Test)

//

// Sometimes it's desirable to build Google Test by compiling a single file.

// This file serves this purpose.Variable Comments

Generally not required if the name is sufficiently descriptive. Often for class variables, more context is needed to explain the purpose of the variable.

private:

// Used to bounds-check table accesses. -1 means

// that we don't yet know how many entries the table has.

int num_total_entries_;TODO Comments

// TODO(kl@gmail.com): Use a "*" here for concatenation operator.

// TODO(Zeke) change this to use relations.

// TODO(bug 12345): remove the "Last visitors" feature.Function Comments

Always write a comment to explain what the function/method accomplishes unless it is trivial. This includes private functions.

- Start with a verb. Eg. “Opens a file…” or “Returns an iterator for…”

- Which arguments can be

nullptrand what that would mean. - Performance implications of how the function is used.

// Returns an iterator for this table, positioned at the first entry

// lexically greater than or equal to `start_word`. If there is no

// such entry, returns a null pointer. The client must not use the

// iterator after the underlying GargantuanTable has been destroyed.

//

// This method is equivalent to:

// std::unique_ptr<Iterator> iter = table->NewIterator();

// iter->Seek(start_word);

// return iter;

std::unique_ptr<Iterator> GetIterator(absl::string_view start_word) const;Class Comments

Always write a comment to explain what the class’ purpose is and when to correctly use it. Always do this in the .h file, leaving comments about implementation detail to the implementing .cc file.

- Good place to provide a code snippet illustrating a simple use case.

- About documenting the

.hheader file vs. documenting the.ccsource file- Document how to use the function in the header file, or more accurately close to the declaration

- Document how the function works (if it’s not obvious from the code) in the source file, or more accurately, close to the definition Source.

// Iterates over the contents of a GargantuanTable.

//

// Example:

// std::unique_ptr<GargantuanTableIterator> iter = table->NewIterator();

// for (iter->Seek("foo"); !iter->done(); iter->Next()) {

// process(iter->key(), iter->value());

// }

class GargantuanTableIterator {

...

};Flashcards

Some simple Q-and-A notes to be used as flashcards.

- What is separate compilation?

- A division of a larger project into smaller units that interact with each other through header files. One unit only knows about another unit through their header files. The big benefit of structuring projects this way is to allow for compilation to be done independently on these units, meaning that if one unit changes while others have not, then only that one unit is to be compiled.

- What are the differences between copy, list and direct initialisation?

- They’re the 3 ways initialisation of a new variable is done in C++. Copy initialisation is done with

=, list initialisation is done with{}, and direct initialisation is done with(). Copy initialisation invokes the . Direct initialisation is directly invoking the constructor, hence the use of().

- They’re the 3 ways initialisation of a new variable is done in C++. Copy initialisation is done with

- What is the difference between

constandconstexpr? - What happens when an identifier is declared outside of a namespace?

- That identifier becomes globally scoped, i.e. part of the global namespace. It can be referenced directly or with

::to explicitly say it’s from the global namespace.

- That identifier becomes globally scoped, i.e. part of the global namespace. It can be referenced directly or with

- Explain RAII and what problem it aims to solve.

- Resource allocation is initialisation means that any resources (things like file handles, database handles, etc.) required by a class should be acquired in the constructor and then released in the destructor. Think of it as “scope-bound resource management”. The point here is that when a class throws an exception or goes out of scope, the destructor is called, guaranteeing no resources to be held after the object’s lifetime.

- What are designated initialisers in C++? How do you use them?

- How do you define a custom exception in C++?

- Write a new class that inherits from

std::exceptionand implement theconst char* what() const throw()method and implement a constructor that takes in an error message.

- Write a new class that inherits from

- Explain copy elision.

- What problem does a move constructor solve — when would you use one?

- What is a const method and why would you use it?

- A const method is one where

constis placed at the end of the function signature. It basically says the method will not modify whateverthisis. As a caller of a const method, you can trust it won’t mutate the object it was called on (although you still can’t be 100% certain because themutablekeyword exists, which lets the const method mutate specific fields anyway, and there are other ways even without themutablekeyword, I think).

- A const method is one where

- When would you write a function that has a

constreturn type?- Pretty much never.

- What are inline functions? Why would you use them?

- What are aggregate types? What are POD types?

- Explain the differences between classes and structs.

- They’re basically the same, except the members in classes are private by default whereas the members in structs are public by default. Note that this difference is only for C++. In C# which also has classes and structs, the structs are also value types, meaning that they’re passed-by-value instead of by reference.

- Explain lvalues and rvalues.

- Explain what the access modifiers do in inheritance.

- How do you make a class abstract in C++?

- Give it at least one pure virtual function. E.g.

virtual void foo() = 0;.

- Give it at least one pure virtual function. E.g.

- What are the differences between virtual functions and pure virtual functions? How does this differ between C++ and other languages like C# or Java?

- Virtual functions are those that can be overridden. Pure virtual functions are those that must be overridden. In other languages like C#, all methods are virtual by default. In those languages, pure virtual functions are known as abstract functions.

- How do you use

overridein C++? What’s the point? - Why is the output of the following program “Something”?

class Parent { public: virtual void do_something() { cout << "Something\n"; } }; class Child : public Parent { public: void do_something() override { cout << "Overridden\n"; } }; int main() { Parent foo = Child(); foo.do_something(); return 0; }- If this code were written in Java, the output would be “Overridden”. In C++, we have object slicing. If you wanted to get this C++ to output “Overridden”, you’d have to use pointer types or references.

- Explain 3 ways the

deletekeyword is used.- Deleting memory-allocated objects:

delete obj;, deleting arrays:delete[] my_arr;, declaring deleted functionsvoid foo() = delete;. Deleted functions are mainly used to suppress operations and constructors, mainly. E.g. you’d mark an overloaded operator method as deleted to prevent the misuse of it.

- Deleting memory-allocated objects:

- Explain const objects.

- Object variables declared with the

constqualifier

- Object variables declared with the

- What are the uses for

final?- It can be used to declare final methods and final classes. Final methods can’t be overridden or changed by child classes. They’re declared like this:

void foo() final;. Final classes cannot be inherited. They’re declared like this:class Foo final;.

- It can be used to declare final methods and final classes. Final methods can’t be overridden or changed by child classes. They’re declared like this:

- Explain

friendin C++ — what do they do and how do you use it?- Inside class

Foo, usefriend class Barto grantBaraccess to every member ofFoo. “Friends can touch your privates,” and “you can’t grant yourself access to other people’s privates, but you can grants others access to yours”. It’s use is discouraged, but sometimes it’s helpful for unit testing classes to access private methods.

- Inside class

- Explain lvalue and rvalue references.

- Write a valid function signature for: a copy constructor, copy assignment operator overload, move constructor and move assignment operator overload.

Foo(const Foo& other),Foo& operator=(const Foo& other),Foo(Foo&& other),Foo& operator=(Foo&& other).

- What is std::move?

- It’s a function you use to help you invoke the move constructor or the move assignment operator. It converts an lvalue to an rvalue reference. It doesn’t do any actual moving itself.

- What’s

thread_local? - How do you define a function template?

- How do you define a class template? How do you define the methods of a class template outside of the class definition?

- What are value arguments in template definitions?

- You can make function or class templates take in a value in addition to type arguments. E.g.

template <typename T, int N>.

- You can make function or class templates take in a value in addition to type arguments. E.g.

- What are functors?

- Functors are also called function objects.

- How are functors and lambda functions related?

- Lambda functions are basically anonymous functors.

- In lambda expression

[&, foo] () { ... }, what does[&, foo]mean?- It’s a capture group, which is a list of identifiers from the containing scope that should be accessible within the function body. The

[&, foo]means that all identifiers should be accessible by reference, except forfoowhich should be copied.

- It’s a capture group, which is a list of identifiers from the containing scope that should be accessible within the function body. The

- What’s the difference between plain enums and enum classes? Which one should you generally prefer?

- What is the

externkeyword in C++? - What is the type of

foohere?auto foo = { 10, 20, 30 }; - What’s different about switch-case statements in C++ compared to other languages?

- You have to wrap each case in curly braces. E.g.

case foo: { ... }.

- You have to wrap each case in curly braces. E.g.

- Should you always use range-based for loops?

- In general yes, but with exceptions. Eg. you should not use it when you are erasing values, inserting something into the middle of something, etc., basically anytime you need to manipulate the position of the iterator, you’d have to fall back to the ugly for loop.

- What are the 5 main iterator categories? How do they relate to each other?

- They are: input, output, forward, bidirectional, random access.

- Why should I use

make_uniqueto createunique_ptrs instead of directly constructing them usingnewlike in:unique_ptr<Foo>(new Foo(...))?- It’s exception safe, meaning if

foo(unique_ptr<X>(new X), unique_ptr<Y>(new Y))fails, there are no resource leaks. It avoids usage ofnewanddelete, which is always recommended for modern C++ code. It’s more readable since you specifyFooonly once compared to twice:make_unique<Foo>.

- It’s exception safe, meaning if

- Explain the difference between

unique_ptrandshared_ptr.unique_ptrrepresents sole ownership whileshared_ptrrepresents shared ownership. Aunique_ptrdeletes the object it’s hosting once it goes out of scope. Ashared_ptrdoes the same only if it is the last remaining owner of the object it’s hosting. The copy constructor and assignment operator are disabled inunique_ptrand only allows for move semantics. Inshared_ptr, copy and move are enabled.

Questions

Some questions I have that are answered:

- Why use functors over methods? From what I know, the main purpose of functors is to act as stateful functions. Methods can clearly accomplish the same purpose.

- Why use regular array literal with

[]vs usingstd::array?