A container is a process running in its own isolated user space, that runs an app within. It contains everything required to run the app, which is basically the app’s source code and all its dependencies.

- You can have multiple containers running on the same machine, and they will share the same host operating system services and resources.

- Containers are defined by a manifest file, which details everything necessary to get your app running within it. In Docker’s case, that manifest file is the Dockerfile.

- The best thing about containers, as developers using a containerisation technology like Docker, is that it gives you a lot of confidence that your app will work exactly the same, regardless of what environment it’s running in.

Running in an ‘isolated’ user space means that the container believes itself to be the only process running on the machine and has its own concept of CPU, memory, filesystem, network, etc., much like a virtual machine. Everything else, like what other processes are running on the machine, are not visible from within the container (try running ps from a shell within a container).

Basically, from each container’s point of view, they have an entire operating system to themselves.

Namespaces and cgroups (control groups) are what enable containers able to be run in an isolated user space and have their compute resources able to be monitored and restricted.

Although containers are considered quite light on computing resources, it’ll never match the performance of running the app as a process directly.

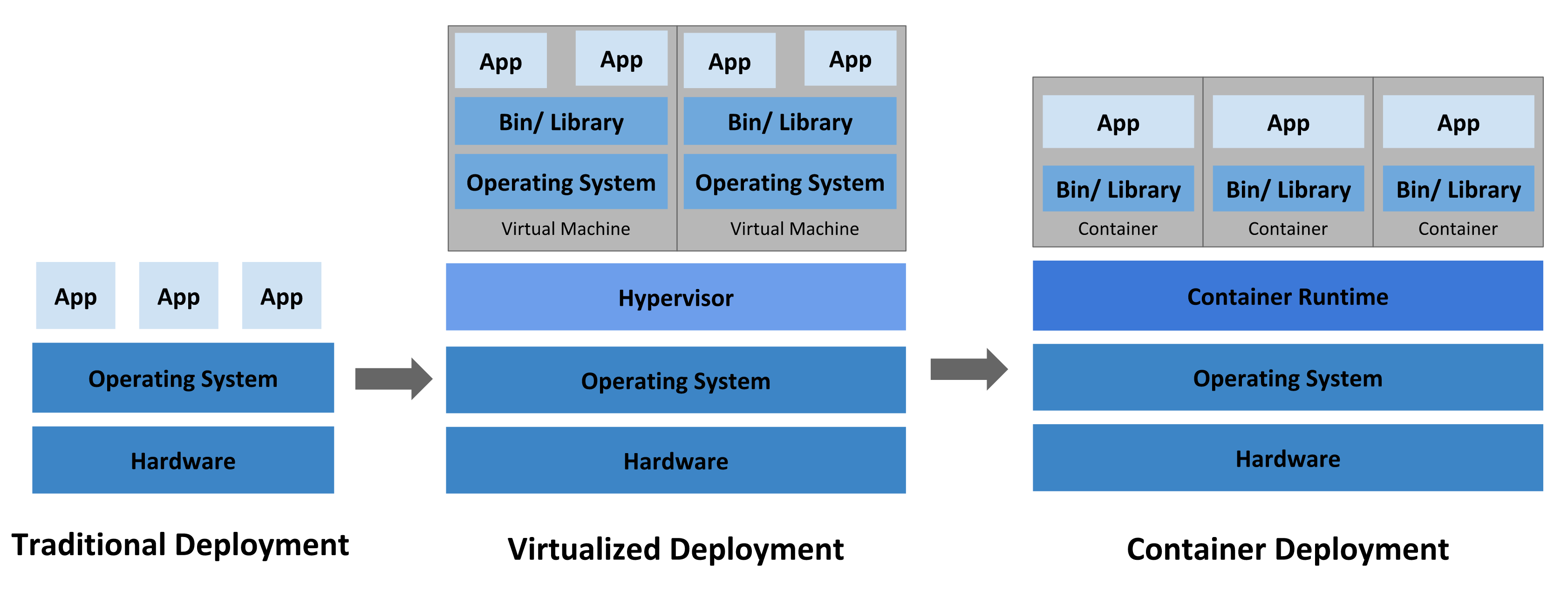

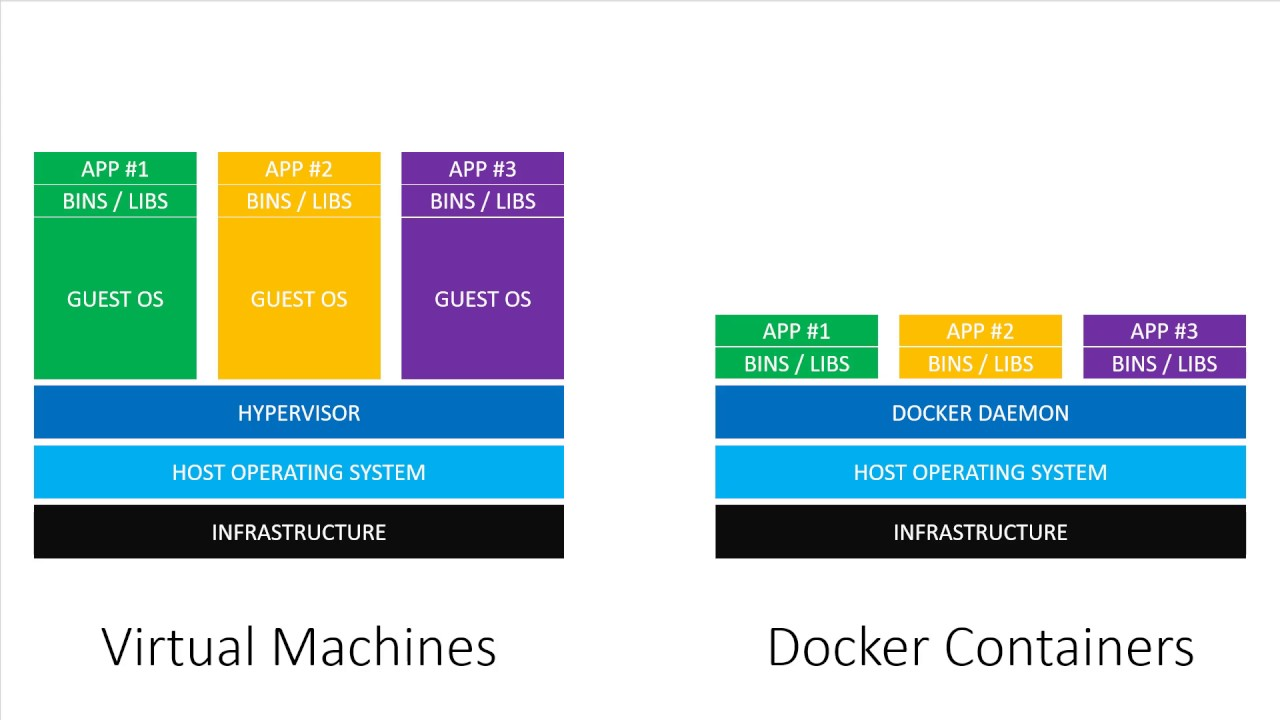

Containers vs. Virtual Machines

Containers are pretty much like system virtual machines, but they tend to use far fewer compute resources (like CPU, memory and disk space) and are quicker to spawn, making them great for on-demand scaling. This is they’re considered substantially more ‘lightweight’ than virtual machines.

When multiple containers are running on the same host OS, they’re sharing the same host OS services and compute resources. When multiple virtual machines are running on the same host OS, they won’t

Deploying multiple VMs onto a single machine will involve creating complete guest OSs and libs for each. There is no sharing of them.

The containers running on the same machine will share the host OS’s resources. Deploying more containers will not mean duplicating guest OSs. You will be able to deploy more containers on a machine than VMs.

Supposing you had 3 services to be deployed, you could either spin up 3 separate VMs, each with an entire OS contained within, or you could spin up 3 containers, each sharing the same host OS kernel services. Both ways would work, but opting for containers is a much more resource-efficient and quicker deployment strategy.

(Image sourced from Nick Janetakis.)

(Image sourced from Nick Janetakis.)

Prior to the widespread adoption of the cloud, the traditional way to deploy an app is simply to set up a physical set of computers in a server room, then run the app on those computers without any virtualisation. This method has a very expensive upfront cost, challenging to scale, and will result in poor utilisation of compute resources. That’s why microservice architectures deployed onto the cloud have become the standard.